Astronomers see the same supernova three times — and predict a fourth to appear in 16 years

The enormous gravitation of a cluster of galaxies warps space to the extent that light from distant galaxies is deflected and brought to us from multiple directions. This effect has enabled astronomers from DAWN and their collaborators to see the same exploding star at no fewer than three different locations in the sky. Moreover, they predict that a fourth image of the same explosion will appear in the sky in the year 2037. The study provides a unique opportunity to explore not only the supernova, but also the nature of the expansion of the Universe itself.

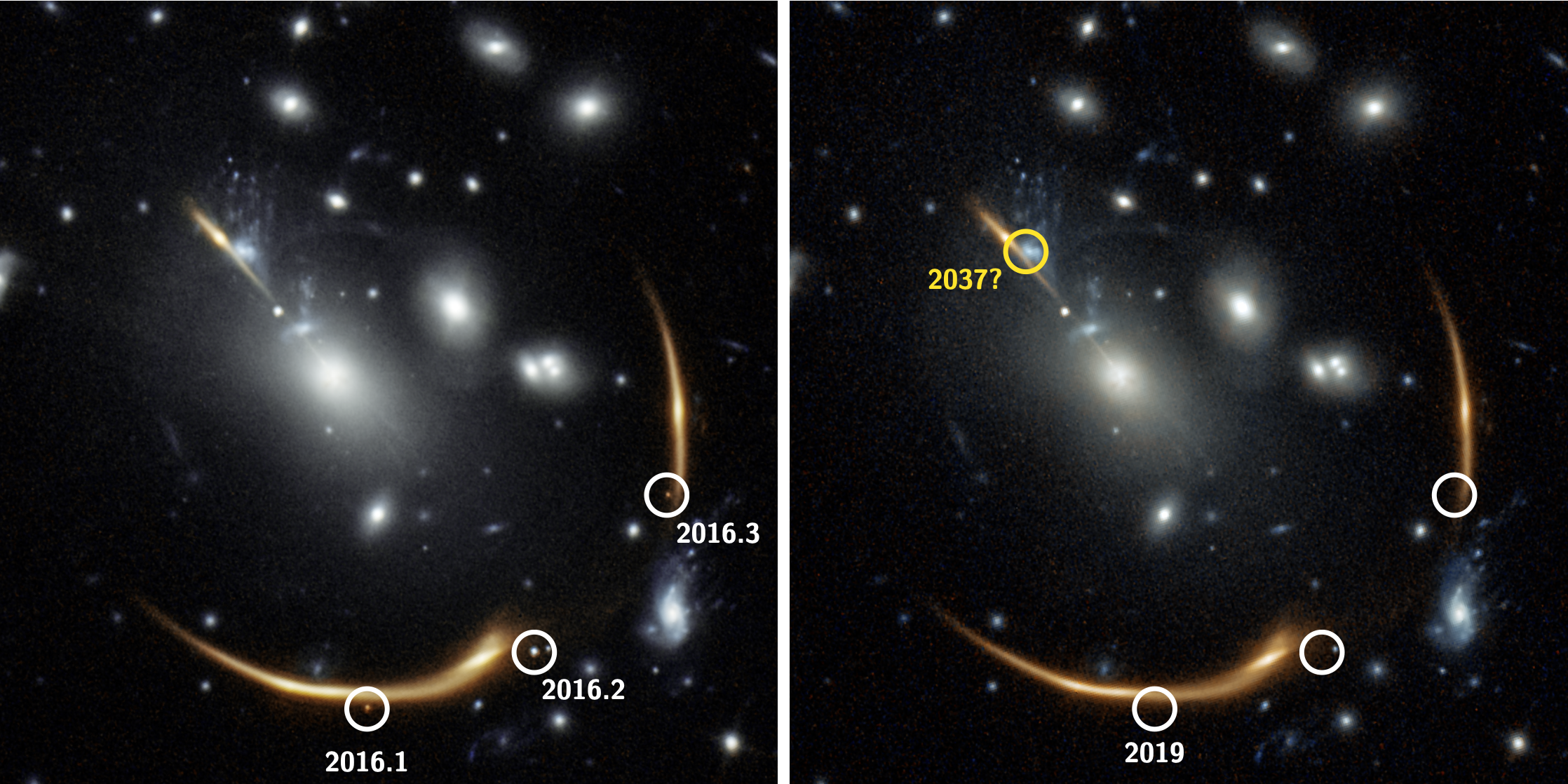

The gravity of the massive galaxy cluster MACS J0138 curves space so that the light from a galaxy behind it is deflected down to us in several different ways. On the left is the observation from 2016, where the light from an exploding star is seen in three locations. On the right is the field in 2019 where the star is seen to have disappeared, but a team of astronomers has calculated that we will see it again in the year 2037 (credit: S. Rodney (U. of S. Carolina), G. Brammer (DAWN), J. DePasquale (STScI), P. Laursen (DAWN)).

One of the most fascinating aspects of Einstein's famous theory of relativity is that gravity is no longer described as a force, but as a "curvature" of space itself. Massive objects curve space, and this curvature not only causes planets to revolve around stars, but also deflect the path of light rays.

The most massive structures in the Universe — galaxy clusters with hundreds or thousands of galaxies — can deflect light from distant background galaxies so much that they appear to be located in a completely different place than they actually are.

And not only that: The light can follow multiple different routes around the cluster, so we may be lucky and see two or more images of the same galaxy, several different locations in the sky through a powerful telescope.

Supernova on repeat

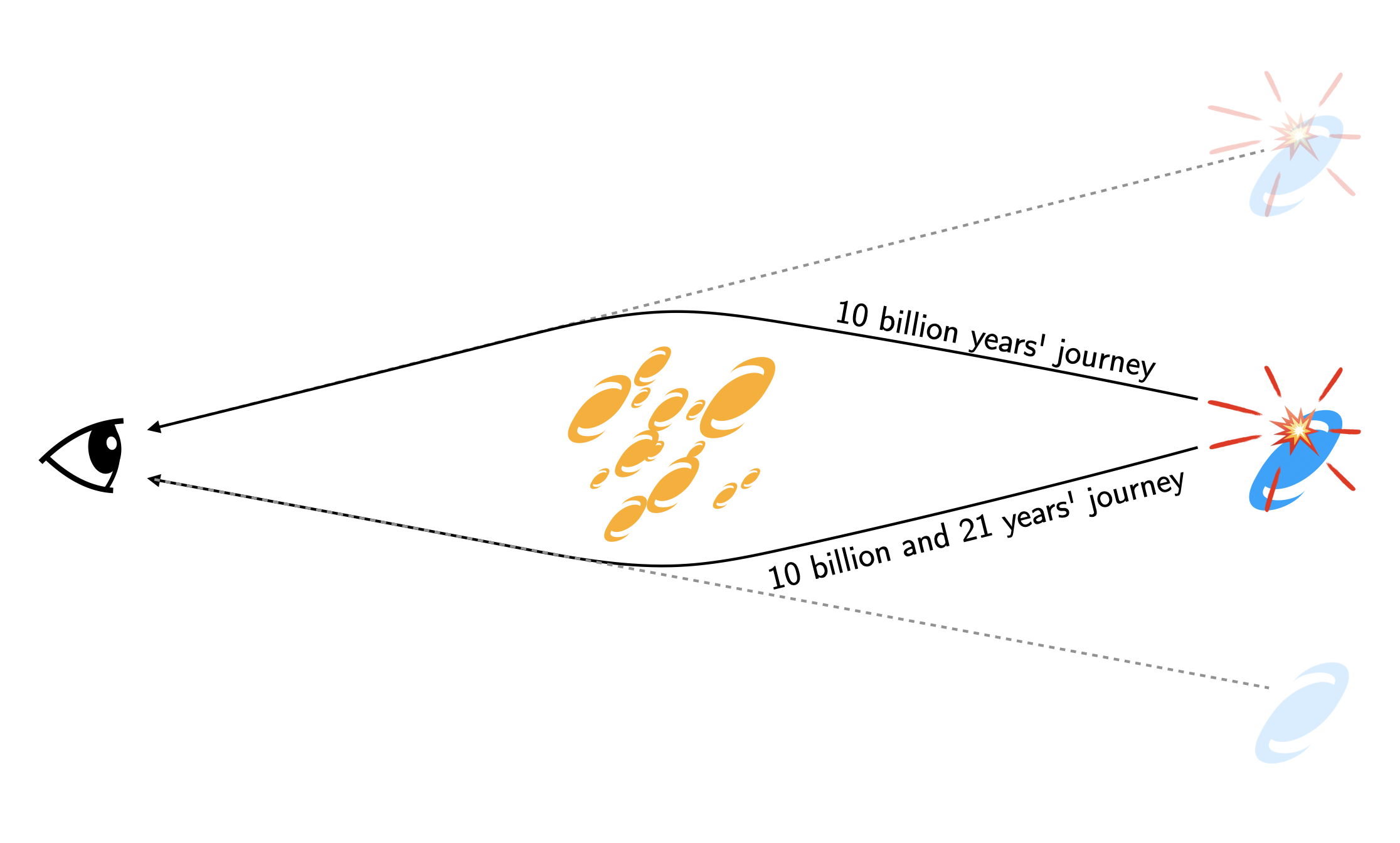

Some paths around the cluster are longer than others, and hence take a longer time for the light to complete. Moreover, the higher the gravity, the slower time passes; another astonishing consequence of relativity. Therefore, it does not take exactly the same time for the light to reach us, meaning that we see the different images slightly shifted in time.

This marvelous effect has allowed astronomers from the Cosmic Dawn Center — a basic research center under the Niels Bohr Institute and DTU Space — and their international team of collaborators to observe a galaxy no fewer than four different places in the sky.

The observations were performed in the infrared wavelength region with the Hubble Space Telescope.

Analyzing the Hubble data, the research team noticed three light sources in the background galaxy that were apparent in an earlier set of observations obtained in 2016, but that had disappeared by the time Hubble revisited the field in 2019. These three sources turned out to be multiple views of a star that ended its life in a colossal explosion — a so-called supernova.

"A single star exploded 10 billion years ago, long before even our own Sun had formed, and the flash of light from that explosion has only just reached us", says associate professor Gabriel Brammer of the Cosmic Dawn Center, Gabriel Brammer, who led the study along with Prof. Steven Rodney of the University of South Carolina, USA.

The supernova, nicknamed “SN-Requiem”, can be seen in three of the four “mirror images” of the galaxy, and because the light in these images have arrived with a couple of month's shift, they provide three different views of the evolution of the explosion. Looking at the last image the supernova has not yet exploded, but examining the distribution of galaxies in the cluster, as well as how the images are distorted by the curved space, it is in fact possible to calculate how far "behind in time" this image is.

In this way, the astronomers have been able to come up with a remarkable prediction:

"The fourth image of the galaxy is approximately 21 years behind those observed in 2016, and we should therefore see the supernova explode, once again, around the year 2037", Brammer explains.

Light from a galaxy with an exploding star takes on different paths around an intermediate cluster of galaxies before reaching us. The research team has calculated that one path is approximately 21 lightyears longer than the others, and they therefore predict that we will see the supernova again in the year 2037. Click here to animate (illustration: Peter Laursen, Cosmic Dawn Center).

Signposts of cosmic expansion

If we really see the supernova explode in the year 2037 it will not only confirm our understanding of gravitation, but can also shed light on another cosmological puzzle, namely the expansion of the Universe.

We know that the Universe is expanding, and with various methods we can measure just how fast. However, the methods currently don't give the same result, even when considering measurement uncertainties. Could our observational techniques be flawed, or — more excitingly — will we have to modify fundamental physics and our understanding of cosmology?

"Understanding the structure of the Universe is a top priority of the largest ground-based observatories and international space agencies over the next decade. Planned future surveys will cover a large fraction of the sky and are expected to reveal dozens or even hundreds of rare lensed supernovae like SN Requiem," Brammer elaborates. "Precise time delay measurements from such sources provide unique and reliable tracers of the cosmic expansion history that can help reveal the nature of dark matter and dark energy".

Dark matter and dark energy are the mysterious stuff thought to comprise 95% of the contents of our Universe, whereas everything we see is but 5%. Indeed the prospects of gravitational lenses are promising!

More information

Contact person

Press releases and mentions

Published paper

The results have just been published in Nature Astronomy: Rodney et al., "A Gravitationally Lensed Supernova with an Observable Two-Decade Time Delay"

Danish version

To read this news story in Danish, click here.

Tags: Supernovae, Gravitational lensing